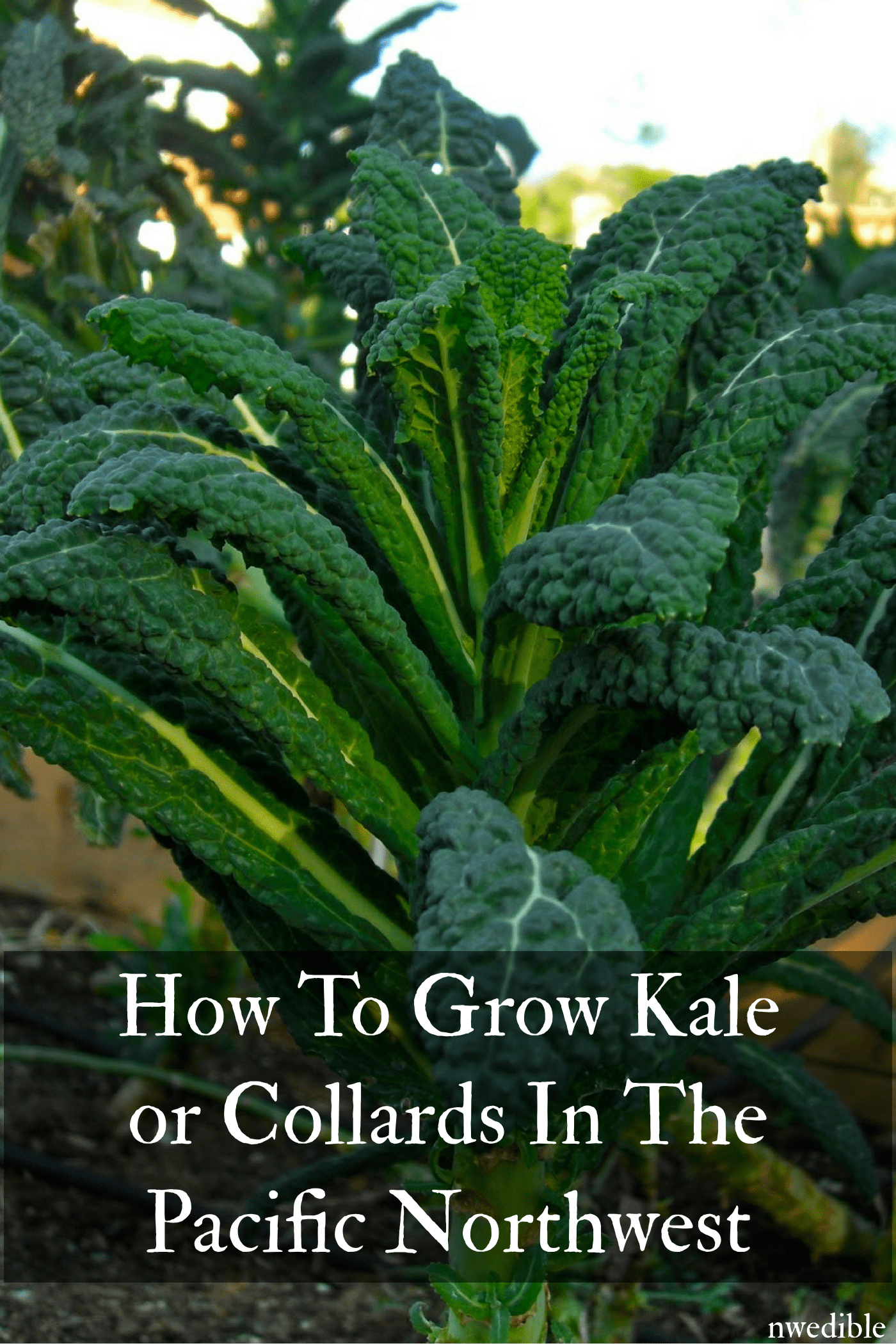

Kale is probably the easiest crop you can grow in the Pacific Northwest. Our cool, mild climate is perfect for kale, which can easily become a year-round source of hipster-approved greens. However, like most cold hardy brassicas, kale tastes best when the weather turns chilly, so if you aren’t a major kale lover, grow this one for fall and winter harvesting.

Kale comes in many varieties and leaf shapes, colors and flavors, so this is a fun crop to play around with – and success is practically assured.

In this article, I’ll be referring mostly to kale, just because that’s what I typically grow and harvest. However, collard greens are grown like, and can be used like, kale. They have the advantage of being a bit more heat-tolerant, so if you are in a warmer microclimate or if summer is particularly hot, collards are a good choice.

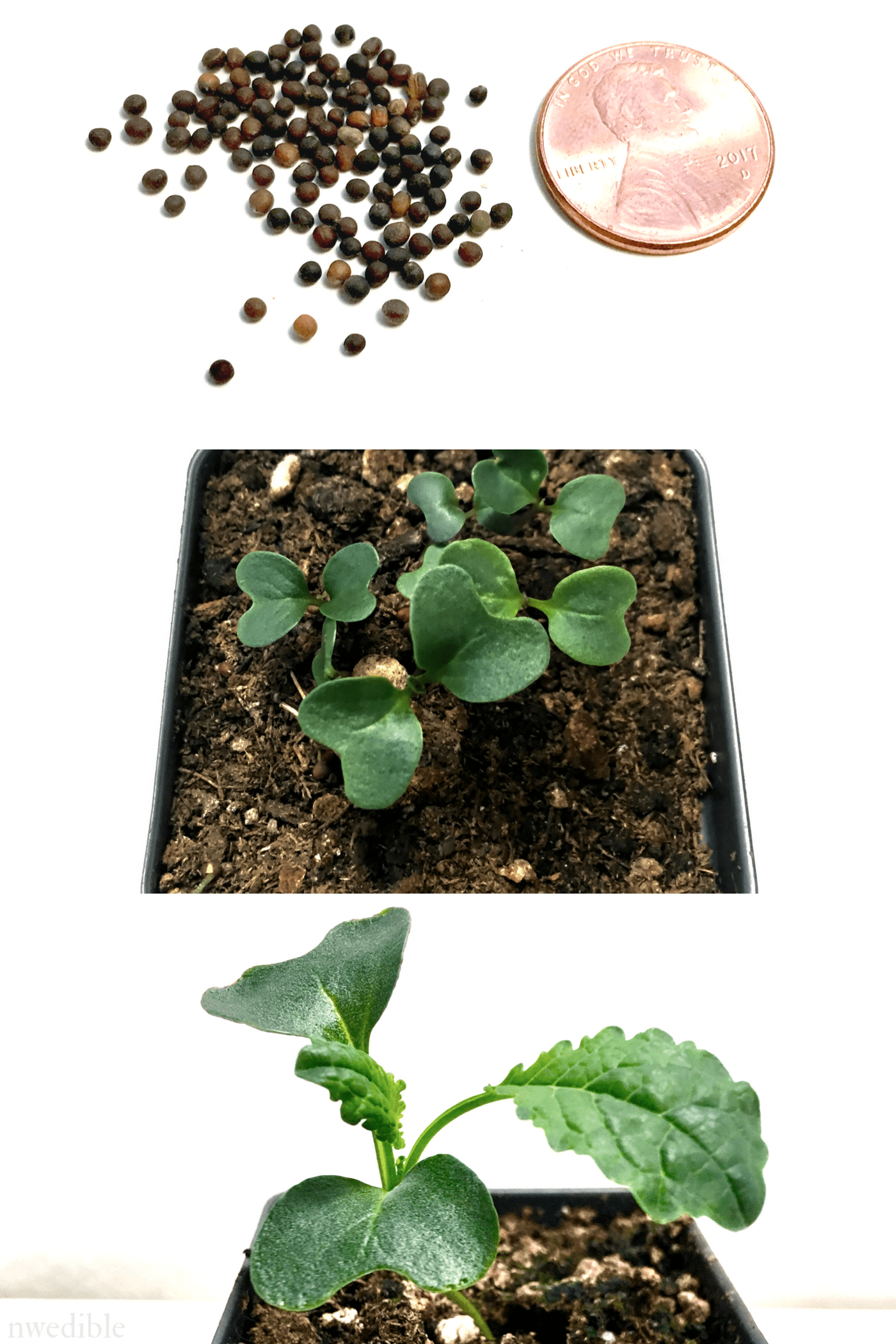

What Kale Looks Like

Like all brassicas, kale seeds are small spheres, medium brown to black in color. The cotyledons (seed leaves) for both have a squatty, heart shape. Below: kale seeds, sprouts with seed leaves only, and seedlings showing the first true leaves.

Kale leaf shape and color is incredibly variable. If you think about the color and shape variety from “ornamental cabbages” that are sold in fall at garden centers, you have some sense of the diversity of leaf shape and color in kales.

Below, four examples of kale leaf shape diversity. In contrast, collard green leaves have a smoother, wider leaf shape. Color on collards varies from quite blueish to a more bright green. I’ve even seen a variegated variety.

Kale Basics

- Common Name: Kale

- Latin Name: Brassica oleracea (Acephala Group)

- Family: Cabbage (Brassicaceae)

- Hardiness: Hardiness varies by cultivar; most varieties can take temps to 18 degrees. The most cold-tolerant types reportedly survive temperatures down to -15 degrees. (It doesn’t get that cold here so I can’t vouch for this.) All kale is typically hardy in the lowland Maritime Northwest with no or minimal protection.

- Lifecycle: Biennial, although in some conditions plants can go to seed their first growing season.

- Season: All, but flavor is best after plants have been exposed to frost, so this is an ideal fall/winter vegetable.

- Days to Maturity: About 21-30 days for baby leaves, 60 for full-size leaves.

- How Hard Is It To Grow? Very easy

Pacific Northwest Specific Tips and Timing

Conditions: Kale is an easy, rewarding crop in the Pacific Northwest. For best results try to give your kale full to nearly full sun, slightly acidic to neutral pH fertile soil, and consistent moisture. However, kale handles a part-sun location, and will tolerate a wider range of soil conditions than many garden vegetables.

Timing: If you start your kale plants indoor in late winter at the same time you’re starting broccoli and cabbage, these plants will be huge come fall, and will likely take you all the way through the next spring. However, summer sowing before mid-July for a fall harvest works fine too.

Season Extension: In higher-elevation regions or during the occasional Arctic blast, row cover or cloching will help your kale make it through the winter.

Kale Seed Info

Typical Seed Life: 4 years, or more if kept consistently cold and dry.

Germination: Kale seed of good vigor should germinate very rapidly, in no more than 4 to 6 days in soil from 50 to 60 degrees F.

How To Plant Kale

Seeds or Starts? Either. Kale germinates well in cool soils, so indoor plantings aren’t really necessary. However, plant spacing is easier if you work from transplants, and starting indoors can help avoid slug and snail damage early in the season.

How Much To Plant: An omnivorous family of four will probably find that 3 – 4 full size plants will give them all the kale they really want. However, real greens lovers and gardeners looking for a large supply of homegrown wintertime greens might plant 4 times this much kale. Between about mid October and mid February your kale will be essentially static, so you should plan on going into the winter with enough full-size plants to see you through whatever quantity of harvest you’ll want.

Starting Indoors: Sow a clump of 2-4 seeds in a pot with generous root room – I like 2-inch square pots. Keep soil temperature moderate – 50 to 60 degrees is plenty warm for strong kale germination, and a bit cooler is better earlier in the season since you’ll be transplanting into chilly soil. 16 hours on and 8 hours off under seed lights works well for growing most vegetables, and I’ve never had a problem with kale following that protocol. Thin to the strongest seedling before the kale starts begin to crowd each other.

Sowing Outside: Plant seeds shallowly, about 1/4-inch deep. For a baby leaf crop, scatter seeds over the soil surface and rake or water them in. For large plants, sow clumps of 4-6 seeds at least 12-inches apart in all directions. Thin to the stockist seedling once your kale is up and growing well and starting to crowd. Alternatively, sow seeds about an inch apart in rows 18 inches apart, and thin kale plants as they start to crowd.

Self-Sowing: If you allow Red Russian kale to go to seed, you’ll never have to plant it again and you’ll never be without it. I haven’t noticed the same tendency with other cultivars, but I can personally attest that Red Russian self-sows like crazy and is a wonderful kale-ful gift in the garden.

Kale’s Growing Needs

Sunlight: Adaptable. In the Pacific Northwest Kale does fine in full sun, but will tolerate part-sun conditions. Try for at least 4 to 5 hours of sunlight per day. In hot-weather climates, kale is best in part-sun, and especially appreciates afternoon shade. Consider collards if you are in a hot-summer climate. They are more heat tolerant and will perform better.

Soil Conditions: Average fertility garden soil with a pH of 6.5 to 7 is fine – although you’ll have more abundant and more tender leaves from rich soil high in humus.

Feeding: For the best growth and most abundant leaves, amend the soil where the kale will grow with compost and complete organic fertilizer (something like a 5-5-5). If leaf production slows during the growing season, side-dress kale with additional complete organic fertilizer.

Watering: Kale prefers consistent moisture. In the Pacific Northwest, I rarely need to water kale before about late June unless it is growing under a low tunnel. Once seasonal rains slow, deep watering about once a week is fine for mature plants; water a bit more frequently for plants that are just getting established, or if you see sign of water stress from your plants.

Recommended Cultivars

Red Russian Kale: My standard, because it self sows everywhere and is very reliable. Fairly tender, even at larger leaf sizes, this is a decent tasting kale but a bit stronger to my palate than Tuscan.

Red Chidori Kale: Not widely sold, this is still one of the tastiest kales I’ve ever grown. That’s odd, because it’s basically an ornamental type, with a low-growing rosette form. Very sweet after a frost, and gorgeous worked into an ornamental edible landscape

Tuscan Kale: Also called Lacinato, Black Kale, Nero di Toscana, Cavolo Nero, Black Palm, Dinosaur Kale and probably a dozen other things. This is the dark green, crinkly, narrow-leaved kale that became a darling of healthy eaters and fancy chefs everywhere in the early-oughts. A mild tasting kale, this one is great in soups, sauteed, or raw as a salad.

Winterbor Kale: Extremely cold tolerant, with very curly leaves. I personally prefer the flatter leaves of Red Russian or the moderate crinkles of Tuscan, but Winterbor is a great choice if you live in a colder region.

Vates Collards: I’m not a collard expert but I’ve grown Vates and found the leaves large, smooth, moderately tough and waxy, and excellent braised in the Southern style. Research tells me this is a good choice if you prefer to cut a few leaves at a time from a mature plant and allow the plant to continue growing.

Flash Collards: Flash is a popular hybrid said to be more tender than Vates, and a good choice if you want to cut the full plant for a harvest of slightly smaller but more tender leaves.

How To Harvest Kale

For baby kale, sow densely and cut swaths of leaves when plants are 3-4 inches tall with scissors. Hold clumps of leaves gently in one hand and snip about an inch above the soil line with the other hard. Leave the plants in the ground, they will regrow for another harvest.

For bunched kale leaves, cut or tug individual leaves from a mature plant downward from the stem. The leaf should separate cleanly from the stem. Select outer, lower mature leaves in good condition and allow the upper, center leaves to continue growing. A very mature kale plant can start to look like a miniature palm tree, with a long, tall, bare stem and a clump of leaves at the top. This is normal.

For whole-plant harvest of kale or (more often) collards, cut the teenage-sized or mature plant through the stem just above the soil level as you would with cabbage. Harvest before the plant starts to grow a distinct, thicker center stem.

Overwintered kale produces loads of kale florets in the spring. These unopened flower buds taste much like sprouting broccoli. More details here.

How to Cook and Eat Kale or Collards

Kale has a rugged, cabbagey flavor with a hint of bitterness. Some people think collard greens are milder and more tender. This may be especially true in hotter-weather climates, but from a culinary perspective these two leafy brassicas have far more in common than not.

Collards have a smoother, wider leaf, so if you are low-carb or otherwise looking for a green vegetable to substitute for flatbread or tortillas, collards are a superior option. Otherwise, collard greens can be used in any of the ways you’d use kale.

Kale can be eaten cooked or raw. Baby kale can be quite tender, but older leaves benefit from tenderizing through salting or massaging if they are going to be used in a salad. Kale is sweetest after it is kissed by frost, so harvests in late fall and early winter are often the best.

I love using kale in a salad – one of my favorite combinations is Tuscan kale paired with roasted sweet potatoes. The bitterness of the kale is complimented and balanced by the sweetness of the sweet potato. I often simply saute kale with garlic then finish with a squeeze of lemon or a splash of apple cider vinegar.

Kale is also a fantastic addition to soups, and pairs well with beans, sausage, and root vegetables. (Recipe: White Bean, Sausage and Cavolo Nero Kale Soup) It can be long-cooked and still retain a nice toothsomeness. Portuguese kale is particularly well-known as an ingredient in soups.

Kale and collards both braise extremely well, and any variation of braised greens or creamed greens can be made with either. Finally, kale sprouts – the tender florets of the kale plant – are a late winter or early spring treat very similar to sprouting broccoli or broccoli raab. Saute with garlic or roast for a delicious broccoli-like dish.

Kale’s Friends and Foes

Pests: All the standard brassica-family pests will bother kale, but typically not to the degree that they will bother more refined brassicas like cauliflower, cabbage, and broccoli.

In my garden, the only substantial pest problem I deal with is the grey woolly aphids that periodically congregate on the growing tips of the kale. These aphids grow rapidly into huge colonies which can distort the leaves and make a “clean” harvest extremely difficult. Collards with their thicker, waxier leaves are said to be less affected by both aphids and flea beetles.

Pests that may bother kale include:

- Aphids – a blast of water will dislodge aphids; a mild soap spray can be used for more severe infestations.

- Cutworms – homemade paper collars made from toilet paper tubes, paper cuts, or foam will prevent cutworms from chewing through seedling’s stems.

- Cabbageworms (More: The Cabbageworm Caterpillar in Your Garden: How To Control It)

- Flea beetles – use yellow sticky traps or a mild, organic insecticide to control.

- Cabbage root maggots – I’ve never had an issue with these on kale, but did lose an entire crop of broccoli from cabbage root maggot one year. Beneficial nematodes (The Steinernema feltiae strain) worked very well for me to control that pest.

- Slugs and snails – use traps, or apply Sluggo. (More: How to Identify and Control Four Common Garden Pests of the Pacific Northwest)

Diseases: I grow a lot of kale, and the only disease I run into is periodic powdery mildew. This typically hits older plants nearing the end of their life span, so rarely impacts my yields much.

That said, most brassica family diseases can impact kale, too. Probably the most serious disease to worry about is clubroot. Prevention is key, so do try to rotate your brassicas, including kale.

Companions: Nitrogen fixers like peas and beans grown vertically behind kale will help provide soil nutrition. Strongly aromatic herbs like basil, dill, and mint confuse and deter sucking-type pests that might bother kale. Garlic and onion are both excellent companions to kale, for the same pest-deterrent reason.

Antagonists: None I’m aware of.

One of my awesome Patrons loathes kale. I’m dedicating this post to her. Sorry Kat. <3

The only comment I would add is that you can hardly get kale in too early. In fact, I usually plant some in July to overwinter and it blasts off in January. Also, many people are surprised to learn that in spring, when the plants seem to be about to bolt with warming temperatures, you can cut off the terminal shoot and all the side shoots will sprout strongly. This gives you a big last ditch harvest before warm weather sets in.

I enjoy reading your posts!

Both Portuguese kale and walking stick kale are going to tolerate warm temps better–our weather is more like California than WA.

And with the Portuguese kale you pictured, those thick white stems are the best part, I promise. Don’t throw them out! A long cut down the middle of the stem/leaf is usually enough to ensure even cooking.

Hee heee! Yep, I’m in the “foes” section for sure!

Oh Kat…me too! I tried to love it and would have tried harder except hubby is totally and diametrically opposed to it because he thinks it tastes “fishy”. ???

I can only add a few things to this great ode to a favorite leafy green foundation plant in my garden. We moved to Northern-Northern Coastal California 18 years ago. I planted Red Russian kale once. I have never planted kale again, except for sprinkling some of the seed heads around. I think this year I counted six different places that kale plants have sprung up in my backyard now, and either RR reverted or I got another plant from somewhere, but I also have what I just call “green kale” growing as well. The hens love it (as well as any yellow flower heads) and besides salads and soups, we love it chopped and roasted with garlic and EVOO then finished with a bit of cream and parmesan in winter, or when I’m overwhelmed with giant leaves I make a nut-butter type dressing, or just EVOO and lemon juice and salt, massage the leaves and dry them in the dehydrator for chips. On lazy nights that’s the only vegetable served for dinner. Kale has definitely “got my back” here.

The Seattle area is NOT the entirety of the Pacific Northwest. Less than 2 hours away, to the east is hot dry desert. Maybe you could specify the coastal or maritime NW…just saying, we’re here too!

Yes, we are. The weather patterns, soil, and arid conditions in our part of Wasco county

make it difficult to translate a lot of PNW gardening advice in ways applicable to our

gardens.

Nevertheless, I find a lot of useful information here, and enjoy following Northwest Edible

life. Keep up the good work

Aw, Phyl please don’t give up on Erica or judge her for living in King County. I’m in Spokane County and can rely on her gardening advice far more reliably than *someone-ahem-who-publishes-in-our-local-newspaper-ahem* for good, solid advice. You can take Erica’s advice and if worried– cross-reference other internet sources and get a really good median of ideas for your area.

I have a very good friend who used to garden near Yakima. She would put pepper seeds in the ground and harvest peppers 90 days later. I thought this was an insane miracle and I didn’t believe it until I saw it. Out here it takes me 6 months to trick peppers into fruiting, and even then it’s iffy.

Most of Eastern Washington has a continental climate, characterized by cold winters and hot summers. Maritime Northwest gardening is characterized by mild, wet winters and dry summers with low heat units. Gardening strategies for these two climates are completely different.

In Eastern Washington, you generally optimize your harvest with super productive fruiting annuals and perennials that thrive with generous heat units combined with very long summer days. If you want to overwinter cool-season crops, extra effort has to be put into mitigating cold during the winter. In Western Washington, we optimize to take advantage of extra-long growing seasons for cool weather vegetables – greens, basically. If we want success with the most heat-loving of the summer vegetables, extra effort has to be put into maximizing heat during the summer.

So it’s a bit like training for a sprint vs. training for a marathon. There is literally no climate specific advice I can give to Maritime Northwest gardeners that will consistently apply to Inland Washington gardeners, or vice versa. We just live in different worlds, climatically.

I hear your frustration at the nomenclature issue – it’s true that Maritime Northwest is a more accurate description than Pacific Northwest for the regionality of gardening advice I can competently offer. Unfortunately, Maritime Northwest is a term that almost no one uses, so it’s just not a great choice for a post title which needs to match up with what people search for.

I do hope you find the more generally applicable gardening information here useful. I am a big fan of Eastern Washington, and am super proud to live in a state where so many key crops – apples, sweet cherries, mint, hops, berries, asparagus, peaches, lentils and more – are grown. Most of those crops are Eastern Washington grown, and literally the whole world benefits from the agricultural success of Eastern Washington farmers.

Beyond that I don’t know what to say other than I can’t be all things to all people and I’m sure there are many great resources specifically for Inland Northwest gardeners. Thank you for your feedback.

The recipes make me want to try and convert myself to liking kale… I honestly think I just haven’t done a very good job growing/buying/cooking it yet. I love the format of this post. It seems like most growing guides, even those in books, are inconsistent about including all the information needed. Thank you for this very complete growing guide and for adding the recipe and cooking ideas.

Well, my chief complaint about this post is that I never saw any information about making Kale taste less “seafood-y”. I am married to a man who is almost completely wonderful except for his taste-buds and Kale isn’t allowed in our diet because it ‘tastes fishy’. So, yeah…after getting a pronouncement like that from him I’m not going to waste my precious teeny-tiny garden space growing it to only have it end up in the compost. But…It is a SUPERFOOD and I want it in our diets. Waaa….any advice? (And also…have you been able to make any progress towards getting the new beautified website to allow for your good old ‘downloadables’ to be accessible again?)

I have no idea how to respond to fishy kale. 😀 That’s a new one to me! I suspect “fishy” is a way of describing the minerality of kale (think “licking a penny” flavor), which can be quite strong depending on growing condition and variety.

Soil with a properly-balanced mineral content (calcium, magnesium, and potassium are major ones) should lead to higher sugar content and better flavor in vegetables. Unfortunately there’s no generic solution to mineral re-balancing in soil – you have to get a soil test and apply amendments in the correct proportion according to the recommendations on the test.

In terms of cooking, one piece of advice generally would be to avoid cooking anything that contains acidic ingredients in cast iron – that can lead to a sorta fishy mineral taste because the acid can leach the iron from the skillet or dutch oven. Kale and other greens aren’t high in acid naturally, but if you cook them with vinegar or tomato in cast iron the flavor can get a bit funky.

Erica, have them cook the kale with garlic and black pepper! I do and it tastes great!

The format of this post is awesome. I feel like I might be able to actually grow kale 🙂 Thanks so much!!!

Hi Erica. Just came across your website. I live in central Alberta Canada and I was still picking kale in my snow covered garden in December last year. The kale was not covered with anything. I was surprised how crisp it remained in my fridge. This year I am experimenting with a few other crops for a winter harvest. Most will probably have to be covered but kale is a workhorse in the vegetable kingdom.

Hi, I’m just starting to grow kale from seed. On my first attempt, I grew it in clear plastic cups. I have several sprouts taking hold and half of what I planted dampened off. I am now using peet pods and watering the seeds with slightly acidic water. I have them on a seed warming blanket. We’ll see what happens with my latest batch. 🙂