Here in the Pacific Northwest, we are typically spared from some of the worst garden pests. Tomato hornworm, squash vine borer, and other veg-destroying insects just aren’t common here.

But it’s not all ladybugs, honeybees and parasitic wasps. We have our fair share of munching critters that can do real damage in the garden. Here’s how to identify and control four of the most common garden pests in the Pacific Northwest garden.

1. Slugs and Snails

Slugs and snails love the Maritime Northwest. In fact, our native slug up here is the second largest in the world – reaching lengths over 9-inches long. Our naturally damp, cool soils, frequent rain, and the deep leaf litter of our native forests make this region slug and snail heaven.

The common garden slugs that bother us gardeners are non-native, and not as wonderfully regal as their native woodland cousins. So don’t feel bad about killing off the brown garden slugs in whatever quantity you can manage.

I’ll refer to slugs, here, but snails are just slugs with a hard hat. Everything said about slugs applies to snails, too.

Telltale Signs of Slug or Snail Damage

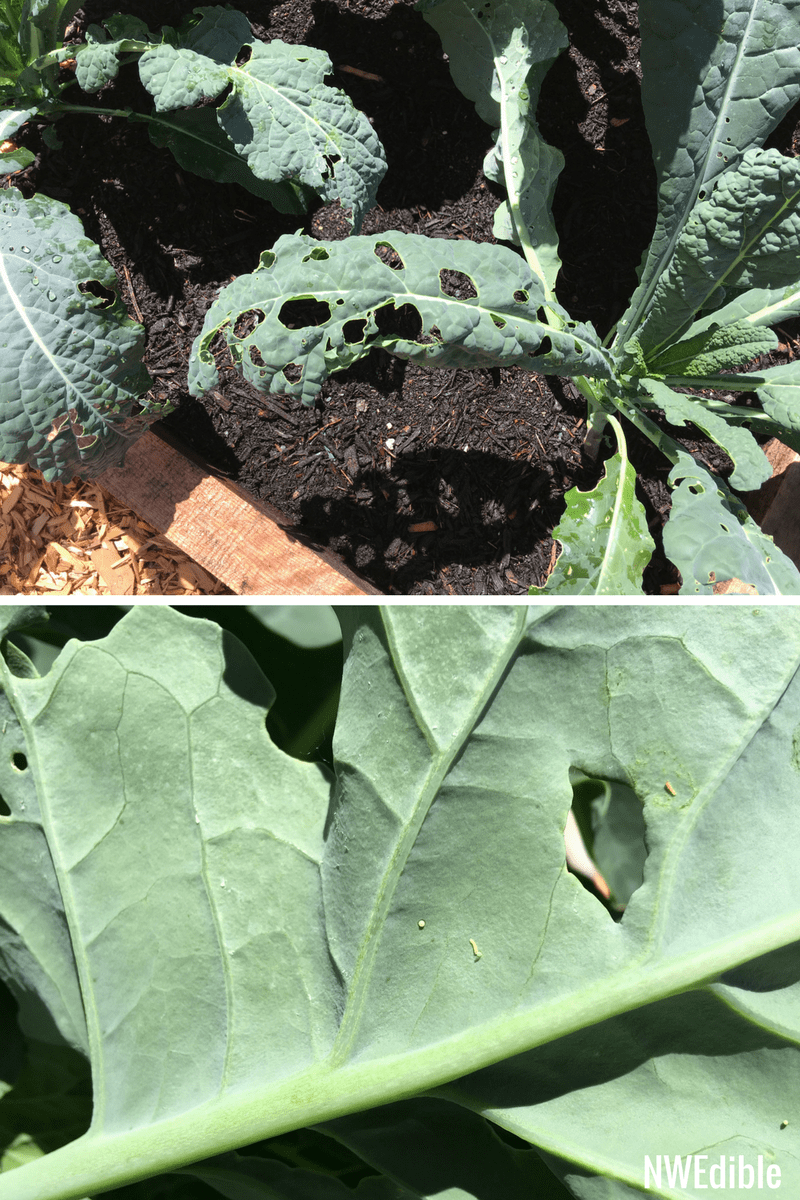

Slugs and snails will eat almost any tender vegetative growth. In the image above, slugs have chewed up the cotyledons of squash plants, but they do not limit themselves to one family of plants. Basically no tender-leaved plant is safe.

Cool, overcast and rainy weather encourages heavy slug feeding. You’re most likely to see heavy slug damage in the spring, before other common pests are a problem.

Look for irregular, ragged holes anywhere on the leaf – edge or center. If you look carefully, you may be able to see traces of dried slime – it will look like a lacy, reflective trail or net under certain lighting. You may also see slug frass – poop – it will look like a small, wet, greenish-brown pellet.

What To Do About Slugs or Snails in the Garden

You’ve got a couple options.

Because slugs prefer to feed in the evening and early morning, out of direct sun, you can go out to your garden after sunset with a flashlight and a sharp pair of small garden snips (I like the Fiskars Softouch Micro-Tip Pruning Snips) and just go on a hunt for slugs. Look under big floppy juicy leaves and when you see a slug, turn it into a matched set of dead half-slugs.

You can also trap slugs by setting out a nice wide board along a path in the early evening. Come out in the late morning, flip the board over, and you’ll find lots of juicy slugs hiding under the board from the sun. You can then dispose of them as you will (dropping the slugs into a bucket of soapy water is effective if cutting them in half skeeves you out.)

If you want to turn your pest problem into eggs, might I recommend ducks? Ducks think slugs and snails are basically ice cream. They are crazy for them. Send ducks on patrol around your garden – not in it while you have actively growing veg, or they will nibble on anything the slugs would have eaten, too – and they will decimate the local slug population in no time.

Your most hands off approach is to apply a molluscicide – a pesticide that targets mollusks, including slugs and snails. The only pesticide I recommend for slugs and snails is Sluggo Original.

Sluggo is organically approved. The active ingredient is iron phosphate – bad for slugs and snails but harmless to everything else in your garden – along with a non-toxic slug attractant. Slugs and snails eat sluggo, then slime off into a hole somewhere and die. Sluggo won’t harm earthworms or beneficial insects, is safe up to day of harvest, and breaks down naturally over time. It’s one of only two insecticides I will use in my garden.

There is another product called Sluggo Plus. Please do not use Sluggo Plus. It’s like Sluggo, but has the addition of a broad spectrum insecticide called Spinosad. While Spinosad is organically approved, its toxicity across a wide range of insects means that you cannot ensure that you won’t be hurting beneficials if you use it.

Here’s Wikipedia on the effects of Spinosad on honeybees:

[Spinosad is] highly toxic to honeybees for 30 days, lethal to egg stage, lethal to larval stage, and causes subsequent queen death; it appears to kill sperm, therefore queens are rendered useless and are soon replaced if the hive survives. Even dried residues have been observed to be lethal to honeybee colonies, whereby honeybees may take up residues from dried sprays in dew which may form on sprayed fruit, foliage, etc. Of 12 hives which were so affected in western Massachusetts in the first week of June, 2015, only two were considered strong when heading into winter, whereas four hives collapsed outright. None of the affected hives was expected to winter over successfully.

So even though Sluggo Plus seems like it might be a cure-all for what ails ya in the garden, I really think the potential cost to beneficials of applying a broad spectrum insecticide just isn’t worth it.

2. Cabbage Moth Caterpillars

Probably second only to slugs up here in the Northwest is the damage caused by a small, bright green caterpillar that devours plants in the brassica family. Called the imported cabbageworm, cabbage caterpillar, cabbage moth caterpillar or – incorrectly – the cabbage looper, this pest is the larval stage of a white butterfly with black spots on its wings called Pieris rapae.

In the Pacific Northwest this pest is particularly problematic because our climate is ideal for the brassica family plants, including broccoli, cabbage, and kale, that the cabbageworm prefers. Lots of food for this pest plus mild temperatures mean several generations of the cabbage moth can hatch out in a single summer.

Telltale Signs of Cabbage Moth Caterpillar Damage

Damage is dramatically more likely to occur on big, tender leaves of plants in the cabbage family. No brassica is safe but in my experience cabbage, Asian cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, kale and collards are more likely to be targeted than radish, arugula, rutabaga or turnip.

The cabbage moth lays her eggs on the underside of leaves that are large enough to support her brood when they hatch out, so typically plants are “teenage sized” before they are targeted for destruction.

Look for chew holes right through the middle of brassica leaves. In heading plants like cabbages, the cabbage moth caterpillar will chew right through the middle of the cabbage, irritatingly maximizing the damage done to the plant.

Both eggs and the cabbage moth caterpillar itself hang out on the underside of leaves. Look at the bottom half of the image and you’ll see both pale yellow eggs and freshly hatched, tiny little cabbage worms on the underside of a broccoli leaf.

What To Do About Cabbage Moth Caterpillar in the Garden

Prevention is very effective. If you’re willing to net all your brassicas with lightweight floating row cover from the minute they germinate or get transplanted out until you harvest them, I can guarantee you will not have a cabbage moth caterpillar problem. That’s too much work for me, but it’s a good option if you are passionate about no spray and you like a Casper the Friendly Ghost motif in your garden.

Hand-picking is very effective for a small cabbage worm infestation. Hand pick the caterpillars that are large enough to get your fingers around and toss them to your chickens. Squish any tiny caterpillars or egg clusters.

Larger infestations of cabbage worm can be managed extremely effectively with a targeted, biological, organically approved insecticide called Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt). Bt is the second of the two insecticides I use in my garden. (See above for the other: Sluggo.)

Bt (pronounced “Bee Tee”) is a special strain of bacteria that paralyses the gut of caterpillars who eat treated leaves. The caterpillars stop eating soon after ingesting the Bt-treated leaves, and die within a few days. It is very effective against caterpillars, but non-toxic to bees and other, non-caterpillar beneficials. It’s safe to use around kids, pets, etc. Just keep it away from any plant like milkweed that might be a host for beneficial butterflies.

I find two targeted sprays of Bt – once in the spring about a week after I first see the Cabbage White Butterfly, and one in mid-summer is usually enough to keep populations of the cabbage moth caterpillar low in my garden.

(Note: some of this information originally appeared in an article about the Cabbage Moth Caterpillar. See that article more additional information, including what beneficial insects to attract to your garden to help in the battle against the cabbage worm.)

3. Leaf Miners

Leaf miners aren’t one specific pest – they are the tiny, maggoty larva of a number of insects. Certain moths, flies, and wasps will, in the larval stage, act as “leaf miners.” The common element is the behavior of the larva: they all chew tunnels through the host leaf from right inside the leaf.

Imagine if a big lovely chard leaf were your bed. Instead of sitting politely on top of the comforter, a leaf miner is gonna slip in right between the flat and fitted sheet. It’s downright invasive.

Different leaf miner larvae are drawn to different hosts. In the Pacific Northwest garden, we are most bothered by Pegomya hyoscyami, the beet leafminer or spinach leafminer. This is the maggot of a small boring fly you’ll probably never even notice. You can probably guess what garden veg it is most likely to attack.

Telltale Signs of Leaf Miner Damage

Beets, chard and spinach are the most likely to show damage. Look for trails or “blotches” of dead leaf. If you hold a damaged parts of the leaf between your thumb and fingers, you’ll be able to feel a little slip or play between the top and the bottom of the leaf. It’s almost as if the leaf has a blister.

Patches of beets or chard are often infected unevenly – you might find one chard plant that is nearly overwhelmed with leaf miner, and one right next door that hasn’t been touched.

What To Do About Leaf Miners in the Garden

Because the leaf miner larva live inside the leaf of your chard or spinach, insecticides don’t do a lot. Apparently, if you are very persistent, and you monitor your leaves carefully, and you use a broad spectrum insecticide, and you spray at just the right time, you might be able to interrupt the life cycle of the leaf miner.

Meh, that’s sounds like too much work, for too little cure and too many possible side effects for me.

Here’s what I do when I notice leaf miner damage: tear off any the part of the leaf that shows damage, looking carefully for fresh damage where the leaf miner has moved to most recently. Give yourself a little margin, tearing off a bit past any damage you see. If an entire leaf is pretty chewed up and blistered, remove the whole leaf. Don’t worry, your plant can handle it.

Now destroy the infected leaves. If you have chickens, feed the leaves to your chickens. Otherwise, burn the leaves, dunk them in soapy water and leave them for a couple weeks, or toss them in your commercial yard waste and let the county haul them away.

4. Pea Leaf Weevils

The pea leaf weevil is a small, dull brown beetle that overwinters on various leguminous host plants. In the early spring, the beetles flies to pea, fava, or lentil crops. To the weevils, a stand of peas or favas is like a big neon sign that says “singles bar” or “I always swipe right.”

The adults congregate, mate and feed on the tender new growth of the pea plants, then the female lays eggs at the base of the pea plant. If weevil populations are high, the adult feeding patterns can stunt or kill pea plants. Typically damage in the garden isn’t that severe.

However, that’s just stage one of the damage this pest can cause. Once the eggs hatch out, the larvae crawl down to the pea plant roots, where they feed on the nitrogen-fixing nodules of the legume for 4 to 8 weeks before pupating. A bad infestation can cause severe nitrogen deficiency in the pea or fava plant.

Telltale Signs of Pea Leaf Weevil Damage

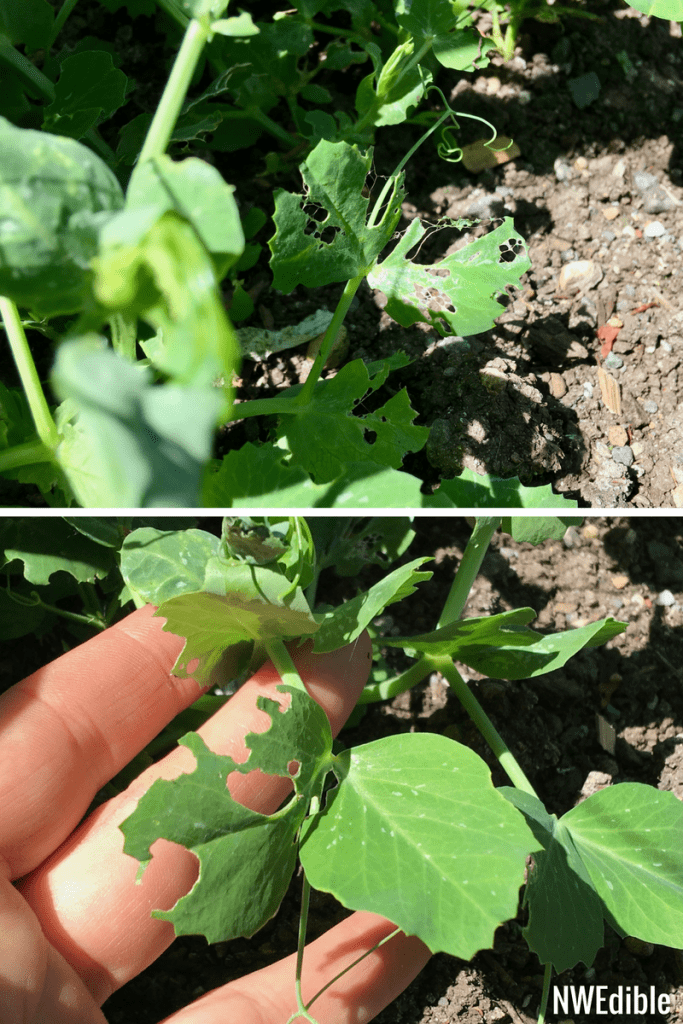

The pea leaf weevil leaves a characteristic notch shape in the leaves of peas, favas, and a few other legumes that are less common in the home garden. Pea leaf weevil damage looks just like someone took a hole punch and punched the edges of the leaf.

The photo above shows signs of damage from two pests – slugs and pea leaf weevils. If you look at the partially shaded leaf in the upper left corner of the lower image, you can see the distinctive notch pattern from the pea leaf weevil clearly. See here for more images of damage, and for a photo of the pea leaf weevil itself.

What To Do About Pea Leaf Weevils in the Garden

You probably shouldn’t do anything. Minor pea leaf weevil infestations don’t usually pose a threat to your harvest. In gardens where the pea plants are not otherwise stressed and have access to continuous moisture and high-nutrient garden soil, the pea plants will outgrow minor damage caused from adult feeding on the leaves, and larval feeding on the root nodules won’t substantially hamper the growth of the plant.

As far as I know, there is no good insecticidal control for the adult pea leaf weevil for backyard gardeners. I mean, there are sprays that will kill the weevil, but you shouldn’t use them.

If the infestation is extremely bad – destruction of the growing tip of the pea plant, or defoliating of your pea crop – cultural control is best. You may have to write off this season’s pea or fava harvest. Sorry about that, but you gotta think long term.

You’ve got about 2 months from when you first see signs of adult feeding behavior on your pea plant leaves until next year’s new pea leaf weevils are pupating in the soil. Set an alert on your phone. When that 2 month timer goes off, fence off your pea or fava crop and turn your chickens loose to go play scratch and peck. The chickens will find all the juicy pupae and larvae in the soil and will help break the pest cycle for next year.

There is evidence that beneficial nematodes will attack and kill the larval stage of the weevil. I’ve never used beneficial nematodes for pea leaf weevils but I have used them very successfully for cabbage root maggot. If you have a persistent issue with pea leaf weevil, I would do some research to see if there is a strain of nematode that would be most useful against pea leaf weevil.

• • •

What pests are the biggest problem in your garden? How do you deal with them?

I recently became a Patreon member and I got a reminder message that I sent myself today to review that decision. Best $1 per month I’ve ever spent. I encourage you all to join!

Thank you Cathy! <3

Great post for this time of year. My sugar snap peas have been making delicious pods for 2 weeks now but recently gone a very light green in both pods and leaves. My first guess is some kind of spider mite or pea leaf weevil. I had so much trouble with leaf miner/weevils in my Swiss Chard last year that I am not growing them this year because i don’t have the resources to create a brassica cage. (Plus I just didn’t love the produce enough to put up a good fight for it this year.) So glad you posted this to give some extra information about fighting this (these) foe(s).

Thanks for this! It’s exactly what I’ve been needing.

Do you know whether ducks can eat slugs that have eaten Sluggo? How about if I am eating the ducks eggs that were made of the slugs that ate Sluggo? Whaddya think?

Most likely scenario? Your diet gets a tiny bit higher in iron, and since nearly all child-bearing age women are low in iron anyway, I can’t see it being a problem. 😉

“Iron phosphate is practically non-toxic to birds, based on testing with quail. Beetles and earthworms were not affected in studies using twice the amount of iron phosphate allowed. Iron phosphate is practically non-toxic to fish, water fleas, and algae. Exposure to bees is unlikely because it is applied to soil as granules.” – Source

I found information that the iron phosphate in sluggo is chelated by EDTA, which is what makes it toxic to slugs, as well as earth worms, dogs and ducks, among other animals.

I’m interested in your thoughts on this information and the quoted sources.

Apparently EDTA was slipped through the cracks in our regulatory system as an “inert” ingredient, and inert ingredients do not have to be listed on the label

Iron phosphate is non-toxic to both humans and dogs, as well as other pets and wildlife. Studies also show that it is equally non-toxic to slugs and snails, because it does not release its load of poisonous elemental iron very easily.

Enter a man-made chemical called EDTA, a chelating agent that causes the iron phosphate to release its elemental iron easily in the digestive systems of not only slugs and snails but of pretty much anything that eats it. EDTA or the similar EDDS are the only reason these baits are effective,

A review of these products by the Swiss organic certification organization (FiBL) discovered the EDTA content and stated that these products were likely no safer than the metaldehyde baits, that EDTA itself was significantly more poisonous than metaldehyde, and even said they weren’t even sure that it wasn’t the EDTA alone that was killing slugs and snails.

http://www.hostalibrary.org/firstlook/RRIronPhosphate.htm

Somehow the link to the source of the first part of my quoted information disappeared in my post:

http://earthfriendlymanagement.com/tag/sluggo/

Thanks for this. I’ve contacted the manufacturer of Sluggo and asked them to respond.

Yep, my ducks are real slug killers! And goodness knows what else they eat, but I have raised hugleculture beds scattered in the yard which I fence off and I hardly ever see slug damage. Now cabbage moth larvae, well let me say I’m off to the intertubes to get some BT. That’s been one of my biggest issues around here. I quit growing any brassicas for three years because they were so bad. This year I’m not seeing any of the white moths tho and have planted some of Carol Deppe’s cut and come again green. So far, so good. And boy are they tasty.

I joined as a patron and this blog just paid for the subscription with the suggestion about BT. The only think I use around here is a service that keeps the carpenter ants from eating the house once every three months, but the house is located downhill from any of the gardens and sometime you just have to bit the weenie and do something your mostly against. They ate a quarter of the downstairs bedroom before I gave up on natural pest control and begged for poison. ugh.

So far however, so good. The only spray four times a year and it’s all at the very base of the house where no one is exposed. The chemical they use is supposed to be pet safe but I don’t let the critters outside for a couple of hours after they spray and the ducks are uphill and upwind, so I’ve not a problem so far. ‘Nuff said. Thanks for the post.

I live in the SF bay area and these are our common pests as well. My son’s college mascot was the banana slug, so go UC Santa Cruz. While I’m sure that some ducks eat snails and slugs, I walk the baylands every morning, and in spite of all the ducks, goose and shore birds, some of the plants are so heavy with snails that the branches droop and break. So glad to have you back, I’ve missed your posts.

Thanks for the info about Sluggo Plus. I was wondering what the difference was, and thinking I should research it. You saved me time and trouble because I will definitely avoid it now!

Such a useful post, thank you. My worst pests this year (Baltimore, md) are the most annoying: white flies on broccoli and spider mites on pole beans. Probably made worse because I am less diligent than with more destructive pests. Still, can’t seem to get a grip on these annoying little buggers (but a mild green caterpillar year so far, thankfully).

Thanks, Erica! Jason Moorehead used the 30% ammonia solution (doesn’t hurt soil) to spray ‘around’ in the evening… worked so so, but the slug ‘crop’ was persistent and large 😉 I have a sawfly whose larvae defoliate the josta berry plant every year…. I always wonder why the birds don’t gobble them up… along with cabbage looper larvae. Must taste awful. Oh, and pill bugs gobble up carrot seedlings. (PS I now have renewed hope for your garden book… it will be so much fun! and I can wait! 🙂

In, northeast Iowa, I planted a lot of dill and some thyme amongst all my brassicas (cabbage, daikon radish, collards) and have zero cabbage moth eggs or worms thus far. By now, for the past several years, I’d have been squishing green worms and cutting off a lot of ruined leaves.

This is a great post! My husband and I are in our first house this year and have seen almost all of these in the garden. We also have raspberries and have started getting small white worms in them. After some research I believe they are fruit flies. We had them last summer too, and I read that they can last from one year to the next. Any suggestions on a safe insecticide for them?