Today’s post is inspired by this reader question that came in from David:

What are acceptable ways for sterilizing canning jars? Most canning books mention sterilizing jars in boiling water. But some folks place clean jars in the oven, slowly bringing them up to 220°F. Is oven sterilization safe? What are the pros and cons of each method?

Let’s get a little nit-picky on language to ensure we are all on the same page. What David is referring to in his question is pre-sterilization of jars. That is to say, ensuring that your canning jars are completely free from live bacteria or other microorganisms before filling the jars with your food item.

Here’s something you might not expect me to say, but it’s almost always unnecessary to actually pre-sterilize your jars before filling them.

Right now you may be thinking to yourself – “Erica, you’re the insane blogger that wants me understand the microbiology of Clostridium botulinum before I make jam and now you’re telling me I don’t need sterile jars?”

That’s right!

If you follow modern canning practices, including processing in a boiling water bath canner or pressure canner for the full recommended time, you probably don’t need to worry about pre-sterilization of your jars ever again.

Let’s take a look at why.

Clean is not the same as sterile

In all cases, your canning jars – for water bath or for pressure canning – must be scrupulously clean. We want perfectly clean jars, with no exceptions. All dirt, dust, and old food residue must be completely removed from your jars before filling. Nothing in this post should be construed as an an excuse to get sloppy with your canning hygiene.

But sterilization is a step further than clean. It’s killing the stuff you can’t see – the germs, the bacteria, the microorganisms. The most common way to sterilize jars – as David noted in his question – is to submerge the jars in boiling water for 10 minutes.

So why is this step not necessary? Well, as long as your canning recipe calls for a processing time at full rolling boil for a minimum of 10 minutes, your jars will be safely sterilized by the act of processing itself. In other words, the important thing is that the jars get a full 10 minutes at the boil, but it’s ok if they are filled with food when that happens.

Since the act of processing will, itself, sterilize the jars, it’s not necessary to start with pre-sterilized jars. Makes sense, right?

Now, there are a few exceptions to this “pre-sterilization not required” advice.

First, if your recipe calls for a very short processing time – anything under 10 minutes – you will need to boil your jars to pre-sterilize. The only thing I know of that has a processing time of less than 10 minutes are some high-acid, high-sugar jams and jellies, which have a processing time of 5 minutes. If you want, you can do what I do and simply process this jam for 10 minutes instead of 5 to avoid the separate, pre-sterilization process.

Second, some recipes will call for a lower temperature pasteurization treatment instead of a boiling water processing. This is primarily something done with pickles where maintaining a crisp texture is very important and high temp processing is more likely to result in a mushy pickle.

In a low-temperature pasteurization treatment for pickles, instead of heating the water to boiling and maintaining a 212-degree temperature for 15 minutes, the water is heated to 180 degrees and is maintained precisely between 180 and 185 for 30 minutes. The pasteurization method is trickier, with less room for error in many ways, and if you are using this technique you’ll want to start with jars that have been fully pre-sterilized.

Thermal Shock

Assuming your canning recipe is such that pre-sterilization of jars is not required, why does every canning book in the world tell you to keep your jars in a pot of simmering water while you prepare your jam or your tomatoes to can?

The answer doesn’t have anything to do with canning safety. At least, not in a preventing-food-borne-illness kind of way.

If you’ve been canning awhile, you’ve almost certainly put a carefully filled and lidded jar of pickles (it’s almost always pickles) into a pot of boiling water, only to hear an ominous pop. You check your pot and there’s sad floating bits of food in the water and one of your jars seems to have completely lost its bottom. That’s thermal shock.

Thermal shock as it applies to canning is when one part of your jar expands faster than another part, causing it to crack or shatter. Rapid change of temperature – typically plunging a cold jar into boiling water – is the most common cause of thermal shock. Keeping your jars pre-warmed in a pot of simmering water until you are ready to fill reduces the chances of a jar breaking tremendously.

(Read More: Help! Why Do My Canning Jars Keep Breaking?)

Is Oven Sterilization Safe?

In his question, David asked about oven sterilization – specifically if it is safe to sterilize jars in an oven by slowly heating them up to 220 degrees. The answer is, no, not really.

The reason has to do with the way heat moves through air vs. through water. Walk through the following mental exercise with me.

Scenario 1

It’s fall, it’s cold out, and you have a perfect batch of chocolate chip cookies in the oven. The timer goes off, so you open the oven door, stick your arm unhesitatingly into the 350-degree oven, and pull out the sheetpan full of cookies. There’s a kitchen towel or a hot pad between your skin and the sheetpan itself, but otherwise nothing between your arm and a chamber of 350-degree air.

What happens?

Well…nothing. You get cookies. Your arm is fine. Your wrist is fine. Unless there is a freak accident, your skin is totally fine. Brief exposure to a lazy pocket of 350 degree air didn’t damage your human-meat-parts in the slightest.

Later you burn the crap out of your tongue on molten chocolate chips because you never could wait for the cookies to cool all the way down and yes mom you were right I should have let them cool off but screw it I’m an adult with my own kitchen now thankyouverymuch.

Scenario 2

It’s fall, it’s cold out, and you have a perfect meal of penne arrabiata planned. The penne is cooking away, the timer goes off, so you plunge your arm, half-way to your elbow, right into the pot of boiling water to fish out your perfectly al dente pasta. Just for consistency, let’s imagine you’re holding a kitchen towel or a hot pad when you do this stupid thing.

Cringing yet?

The water is far cooler than the air in the oven, right? At 212 degrees, boiling water is 138 degrees cooler than our 350 degree oven. But you know instinctively that it’s ok to reach into a 350 degree oven, and hand-suicide to reach into 212 degree water.

What gives? Clearly, temperature isn’t everything, Mr. Potter.

The Science of Heat Transfer

I invoke this simple mental exercise of boiled flesh vs. chocolate chip cookies to demonstrate that it’s not just temperature we care about when it comes to canning – it’s also heat transfer, or the rate at which energy can move from one substance to another.

Simply put, water is far more effective than air as a way to transfer heat into an object. When it comes to canning, we know that a pot of boiling water will transfer enough heat to a glass jar to sterilize it in 10 minutes. We can’t say the same for the air in an oven.

And that doesn’t even touch on oven heat regulation and variability. When I worked as a personal chef I always brought an oven thermometer to my clients’ homes on the first meeting because it’s very common for an oven to run 25 or even 50 degrees hot or cold of what the knob indicates. The temperature gauge on your average oven is about as accurate as a Facebook-linked personality quiz. (But you’re still definitely Faramir, not Gollum.)

So, no, I can’t recommend oven-sterilization. Too many variables.

(Sidenote: oven canning – or doing the actual processing of your jars in the oven – is not safe in any way, shape or form. Do not do this.)

Keeping Jars Warm In An Oven Without Sterilization

But let’s say your goal isn’t to pre-sterilize the jars, but to simply keep your jars warm at around 200-degrees to avoid thermal shock before processing for 10 minutes or more in a boiling water or pressure canner.

Now it gets more complicated.

Some people will tell you the dry heat from the oven will crack jars. This is close but not exactly accurate. Some people will tell you they always streamline processing on smaller stoves by keeping their jars warm in the oven and never have an issue.

I say this is a judgement call situation. Here’s what you need to know.

Remember our old friend heat transfer? Well it turns out that metal has a far higher capacity for heat transfer than air or water. Metal is so great at conducting heat (conduction is simply the transfer of heat between substances that are in direct contact with each other) that we make most of our pots and pans out of it. From searing to cross-hatched grill marks, when we want heat energy to move rapidly in cooking, we usually rely on direct contact with metal.

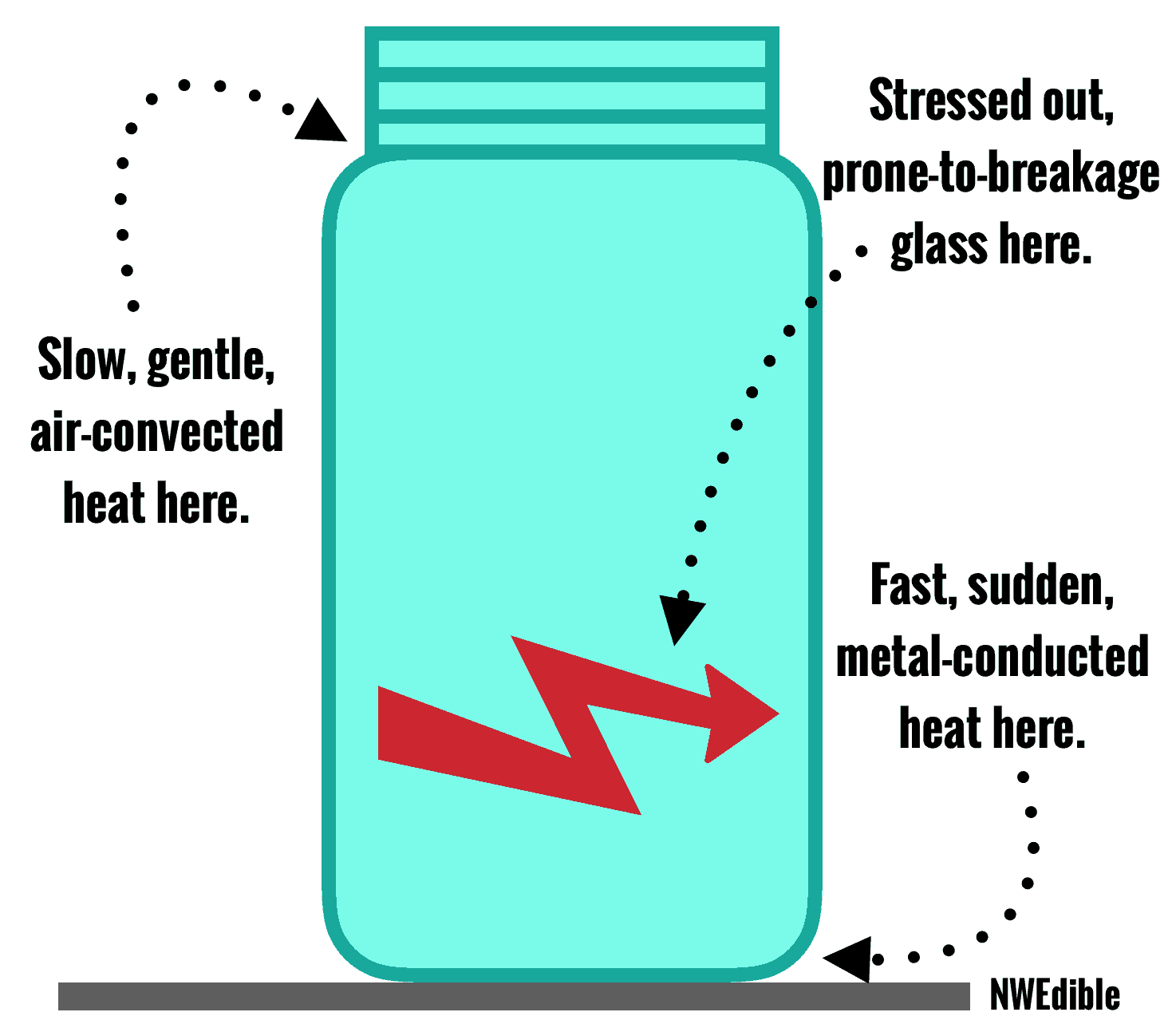

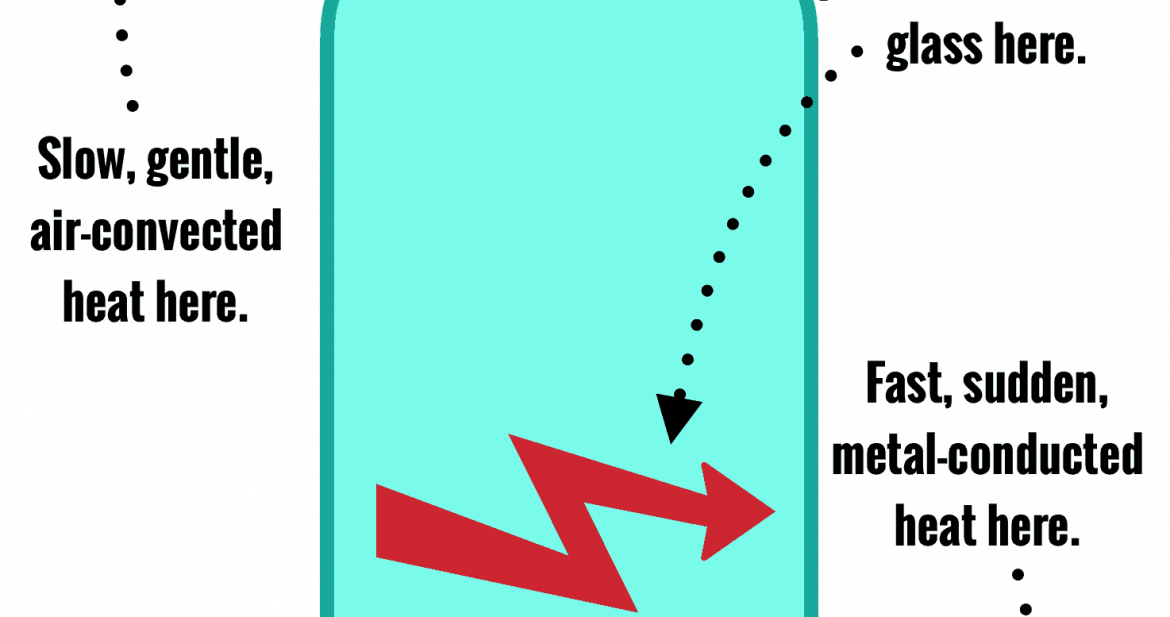

If you place a bunch of empty glass jars on the metal racks of your oven, or on a metal sheet pan in the oven, the metal will heat up and transfer a bunch of energy into the bottom of the glass jars at a far faster rate than the air will be sending energy into the top of the glass.

Unequal rate of energy to different parts of the jar = unequal rate of expansion to the jar itself = the possibility for the kind of thermal stress that can lead to cracked jars.

For my fellow visual learners:

If you have a jar crack from thermal stress in the oven, every jar in the oven has to be cooled, washed and carefully inspected for glass shards.

That’s the real risk. From a safety perspective, keeping your jars warm in the oven isn’t about botulism or flat sour or anything microbiological – it’s about the risk of a jar cracking and sending glass shards flying, and these glass shards ending up in your tomato sauce.

In addition, because of oven temperature variability, it’s quite possible you could under or overheat your glass jars in the oven without knowing it and, in filling them, end up back in thermal shock land.

I don’t go in for oven-warming my jars, but like I say – judgment call.

If you choose to keep your jars warm in the oven, please use an oven thermometer to periodically check that 200 degrees in your oven really is 200 degrees. Mitigate the risk of thermal shock by placing the jars in a deeper, non-metal pan, such as an oven-safe pyrex baking dish, and adding about an inch of water to the dish. The water will mitigate the speed at which the heat transfers to the bottom of the jars and reduce the risk of thermal shock.

Other Options For Keeping Jars Warm

I don’t keep my jars warm in the oven, primarily because I think it’s a gigantic waste of fuel. Mostly, I use the simmering-pot method, which is convenient for the size of canning batches I do.

- Wash your jars very well.

- Put a rack on the bottom of the pot you’ll use for water bath processing.

- Put the jars you’ll be using on the rack.

- Fill everything – jars and canning pot – with hot tap water, put a lid on the pot, and bring everything up to a simmer. Once the canning kettle reaches a simmer, reduce the heat to low.

- In the meantime, prepare your food to can. When you’re ready to fill, turn the heat back up under the kettle.

- Tip the hot water from the jars back into pot, remove the jars from the pot, and fill jars following standard canning practice.

- Proceed to lid and can as per standard canning practice.

I find this method just keeps the canning sprawl contained and efficient. The energy used to pre-heat the water for canning also brings the jars up to a safe temperature. To me that makes more sense than having both the oven and the stove using energy to keep things warm.

You can also run your jars through the high heat cycle on your dishwasher and keep the dishwasher door closed until you are ready to fill your jars. I like this method for really big batches of canning because the jars get both washed and pre-warmed without too much work or lost counterspace.

If your tap water gets very hot, it’s also usually sufficient to pre warm your jars by arranging them in your (very clean!) sink and filling them with your absolute hottest tap water. Heat the water to boiling in a kettle first if your tap water doesn’t get scalding hot due to temperature limiters on your heater.

If you are concerned that your jars have cooled down during filling, just drop the heat under your canning kettle a bit, so the jars are placed into water at a bare simmer instead of a boil. This reduces the temperature difference between the jars and the water a bit. Just make sure you don’t start timer for processing until the water is back up at a full rolling boil.

How do you pre-warm your jars for canning?

• • •

Want To Ask Me A Question?

It’s easy, and I love it when you give me fun things to write about! Just follow these steps to make it easier for me to answer your question:

- Send me an email with “Question for Erica” in the subject line.

- Ask your question in one or two sentences.

- Start a new paragraph and provide any additional details that are relevant to your question.

If your question has broad applicability and I can answer it, I’ll do my best to answer it in a post like this.

This question originally came to me in my recurring role as an Expert Council Member on The Survival Podcast. My Expert Council answers to productive homekeeping and food preservation questions can be found on selected Survival Podcast episodes.

I have often prewarmed the jars in the oven, but lying on their sides on a towel.

If you are worried about how clean your sink is for keeping jars warm then you shouldn’t be using a dishwasher for the same purpose. Modern dishwashers are NOT clean environments, let alone “very clean”. They use neither sufficient water nor generate sufficient heat to be considered clean after a cycle. Sure your plates and glasses look clean and are probably cleaner than you could get them by hand, but unless you have a commercial dishwasher the inside is nasty. (And do is your washing machine)

Typically, I warm up my jars in the water in the canning pot. When I am doing a large batch in the pressure canner, where I do two layers, I will warm at least some of the jars in the oven. Never had one break, but I typically put them in a cold oven and then heat.

I’ve been hand washing and rinsing my jars and placing them upside down on a cookie sheet in the oven at 220 for no less than 20 minutes. Never ever had one crack or explode (thankfully). I think I prefer this to the water method as there’s less scalding water flying around and I can take the whole pan out at once and have the jars ready to flip over and fill right away. I think I’ve always been a little anal about “keeping everything hot”, which I still do, but just not in such a rush about it. I’ve since seen people filling dozens of jars first, before putting all the lids and rings on, and I’ve never done that. I get the idea is to keep bacteria from falling out of the sky into the jars before they’re lidded. Also, and I know this means there are now two reasons why you won’t eat my jams) I do the inversion method of sealing jams with sugar, and also my no-sweetener applesauces. I guess I just don’t like the boiling kettle of water UNTIL I finally used it last year for whole tomatoes, salsa, and pears (oh, and your coriander beets!) and it was all so awesome that I’m doing it again this year for those things, but not for acidic fruits.

I use your method of keeping my jars warm in the pot. But if I pour all the heated water out of the jars into the pot, then fill the jars with food and try to put them back into the pot, I have way too much water in the pot. I’m just wondering if I’m missing something. I hate to use the energy to heat up all the water to heat up the jars, then waste it by dumping it out.

Marc, I pour any extra water into another container and use it to kill weeds, if it’s still really hot.

I have a pretty good idea of how much the filled jars will displace the water in the pots I use most frequently for canning, and fill jars and pot with water to the point a bit over what I expect I’ll need. Sometimes this means the water level is an inch below the lip of the jars before I fill – that’s ok, because the simmering water and steam heat up the jars without issue. Then, after filling, the water level rises to an inch or two above the lids.

That said, I do err on the side of too much water, because it’s easier to take out some hot water than pause processing while I heat more up. Some folks who have efficient electric kettles do the opposite; erring on the side of a bit too little water but they have hot water in their kettle that can be re-boiled in a minute or so if they need it.

What an exciting post! Who knew that you would explain the coefficient of expansion by using canning as an example!

I learned all these physics as a lampworker so my glass beads and sculptures don’t crack.

I usually warm my jars in the oven, starting with a cold oven and progressing slowly to about 200F. I dislike heating jars in the water in my canning pot, because I find that the water can leave hard water marks/spots, and also because I like my jars completely dry before I fill them. I have not yet had any issues/breaking of jar bottoms….hopefully things stay that way!

Great article, fun analogies.

I’ve tried the oven thing and didn’t have any issues but didn’t like the wasted energy and the extra heat in the house but now I know why it not the best of plans. And you know what they say, knowing is half the battle :p

An incredible and very interesting introduction to canning, Erica. I like the way you explained the heat transfer. I used oven for pre-sterilization of my jars, and what I do is to cool it down before putting it into my pressure canner. Because of this article I may have to stop doing that, because using oven for pre-sterilization is a waste of gas. Thank you very much!

I have read about microwave sterilzation, have you ever used that?