Today’s post comes to you from Bill Whitson. Bill is the co-owner of Cultivariable Seeds, an independent breeder and supplier of seeds and plants, specializing in Andean vegetables and other unusual and hard-to-find edibles for the Pacific Northwest. He was kind enough to put together this incredible primer on cultivating oca, yacon, mashua and ulluco for folks in the Pacific Northwest and beyond.

If you’re ready to move past the potato and explore some of the other root crops of the Andes, Bill is an honest expert and I’m so grateful he shared his knowledge here. If you want to try these unusual edibles yourself, you can still buy seed tubers of these crops from Bill, but don’t delay because they can’t be shipped past mid-April.

One of the biggest benefits to growing some of your own food is that you have a chance to try different varieties and even different crops than you would find at the grocery store.

Sure, your grocery store has carrots, but they probably don’t have white, yellow, and purple carrots alongside the ubiquitous orange varieties. Depending on how fancy your local grocery store is, tomatillos and rutabagas might be exotic, or perhaps you live in an upscale salsify and horned melon zone. You might come across even more unusual items on occasion, but you’re far more likely to encounter truly unusual edibles for the first time in a seed catalog.

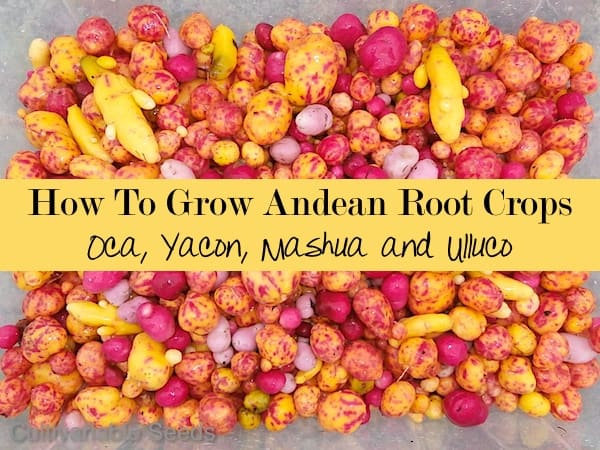

Fourteen varieties of oca tubers.

I first read about the Andean tuber oca about fifteen years ago in an Oregon Exotics catalog. That led me to a battered copy of the book Lost Crops of the Incas, where I learned about many other such crops: achira, ajipa, arracacha, maca, mashua, mauka, ulluco, and yacon.

All were cultivated along with the potato in South America before the arrival of the Spanish and they were all brought to Europe at various times, but only the potato managed to penetrate European agriculture.

Searching out sources of seed for these crops has been a long and sometimes frustrating journey. In the past five years or so, there has been an explosion of information on the Internet about these crops, which has made it much easier to find varieties to grow, improved collaboration between growers. This has resulted in Andean root crop breeding projects outside of South America which should eventually improve the suitability of these crops for lowland temperate climates.

If you’ve ever tried to grow unusual crops in your garden, you’re probably wondering if these Andean vegetables are worth the effort. There is often a reason why uncommon crops are uncommon. I have a rule of thumb for “alternative” crops: If it tastes good, it grows poorly and if it grows well, it tastes bad.

The Andean crops are not exempt from this generalization, although the Pacific Northwest turns out to be one part of North America where we can grow these crops with a reasonable assurance of success…most of the time.

The Climatic Needs of Andean Root Vegetables

Let’s do a quick review of climate and geography and then I’ll get to the roots of the matter. The Andes are a high mountain range in tropical South America, stretching from Venezuela to Chile. The crops that we are going to discuss are grown at elevations from about 9,000 to 14,000 feet. For purposes of comparison, Mount Rainier is 14,409 feet tall.

It turns out that the lowland Pacific Northwest and highland Andes have a lot in common, climatologically. Both have cool climates that are not particularly cold in the winter or hot in the summer. Both have a wetter side and a drier side, defined by the the ridges of the mountains and produced by uplift of marine air against the west side of the mountains.

The area of the Pacific Northwest west of the Cascades is very similar to the cultivated regions of the Andes with two exceptions: we have stronger frosts in the winter and we have much greater variation in day length due to our much greater distance from the equator.

These two differences add up to one major concern for the grower of Andean root crops in our climate. Because there is very little change in day length in the tropics, most of these plants are adapted to conditions of equal day and night length.

They don’t begin to form tubers until after the fall equinox (about September 22nd) in our part of the world, since this is when day length drops below 12 hours. Unfortunately, in much of North America, the first frost is not too far off by that point. So, to grow Andean root crops outdoors in North America, we need a climate that has mild summer and winter temperatures and a frost-free growing season through mid-November.

Many parts of the Pacific Northwest and coastal California can satisfy this requirement, particularly if you are willing to extend the season by adding some frost protection like a low tunnel or frost blankets.

These are generalizations that apply to all of the Andean root crops, although the details for each are a little bit different. So, without further ado, let’s move on to the plants.

A Tour of The Tubers

I named nine Andean root crops above and will discuss only four of them in this article: oca, yacon, ulluco, and mashua. These four crops can be obtained in North America without too much struggle and grow well in the right environment. Achira, ajipa, and maca are also available but better varieties probably need to be produced before they will appeal to most gardeners. Arracacha and mauka are extremely difficult to obtain (although not impossible) and there is very little information about growing them in North America.

There are a few things that all of these crops have in common:

- They are tuber-forming crops. Each produces storage roots in the fall. You dig them just like you would potatoes.

- All are started in spring by replanting seed tubers rather than true seeds, just as you would do with potatoes.

- They are perennial, in that they regrow from tubers. Where the ground doesn’t freeze more than an inch or two, the tubers will survive the winter in the ground.

- They are generally immune to diseases that make potatoes difficult to grow, like blight, although oca and ulluco do share some viral diseases with potatoes.

Oca (Oxalis tuberosa)

Oca is the most widely available of the Andean root and tuber crops in North America. While it is always perilous to set expectations with comparisons, it is quite similar in form, usage, and cultivation to the potato.

Oca tubers are about the same size as fingerling potatoes. They come in a wide variety of colors, particularly whites, yellows, reds, and purples. Many have contrasting eyes or other patterns on the skin.

The flavor is commonly compared to a potato with sour cream already added. Cooked oca is slightly softer than potato, with a bit of acidic tang. The amount of tanginess can be controlled by exposing the tubers to sunlight, which reduces the acidity.

Oca is generally a good substitute for both potatoes and carrots in cooked dishes and it can also be eaten raw. Smaller pieces are crisp and lemony while larger pieces are watery and starchy like raw potato; best to slice your raw oca thinly.

Oca plant in a half barrel

The oca plant grows to be about 18 inches tall and has about a two foot spread, which is similar to a late potato plant. It grows best when high temperatures stay under 80 degrees, although it can survive brief periods of temperatures into the 90s or even the 100s.

Oca needs plenty of water early and late in the season, but is otherwise reasonably drought tolerant. If you can grow a late potato, you can probably grow oca. The size and quality of your crop will depend on how long you can keep it frost free. If you can make it to mid-November, you will get a decent crop. If you can get to mid-December, you will probably have a bumper crop.

Harvest is best done no sooner than two weeks after the top of the plant is killed by frost. The roots draw carbohydrates from the dying foliage and tubers continue to increase in size until this process is complete.

Nutritionally, oca is very similar to potato, but is lower in calories and has more vitamin C. Oca’s tanginess is produced by oxalic acid, an antinutrient found in many foods. The level of oxalic acid in oca varies significantly by variety and with the amount of sun exposure the tubers receive, but the varieties available in North America are roughly comparable to spinach in oxalic acid content. If you have a health condition like kidney stones or gout and have been advised to limit oxalic acid, it is probably best to avoid oca. For everyone else, if spinach, carrots, and potatoes give you no trouble, oca shouldn’t either.

Interior of an oca tuber

There are at least 28 heirloom varieties of oca in North America (that is the number we have in our collection) and new varieties are now being bred from seed as well. I recommend the varieties Sunset, Hopin, and Bolivian Red as top choices for first time growers.

Yacon (Smallanthus sonchifolius)

Yacon may be overtaking oca as the most well known of the Andean tubers other than the potato. It has recently featured in some popular weight loss claims (more on that below). Yacon is a relative of the sunflower and will be very familiar to anyone who has grown another sunflower relative: the Jerusalem artichoke or sunchoke.

Yacon may be the most adaptable of the Andean vegetables to North America; it can tolerate a lot of summer heat as long as it has water. Yields are lower in warmer climates, but it is a very high yielding plant to start with.

Plants grow to be at least five feet tall and perhaps up to twice that (some varieties are taller than others), with large diamond shaped leaves.

Mature yacon tubers at harvest.

Yacon makes very large storage tubers – up to twice the size of a large baked potato. These are typically eaten raw as a fruit. The tubers are crisp and juicy with a mildly sweet flavor that may remind you of less-sweet pear or watermelon with an aftertaste of celery. That may sound strange, but it doesn’t seem to be an acquired taste; most people like it the first time that they try it.

Yields can be very high – as much as 20 pounds per plant where cool summer temperatures converge with plenty of sun and abundant water. Unlike the other three plants, yacon begins to form tubers before the autumn equinox, but they grow fastest in the fall when water is plentiful, so yacon still benefits from a long season.

So, what about those weight loss claims? As with most such claims, there is some truth beneath the hype. Like Jerusalem artichoke, most of the sugar in yacon is stored in an undigestible form: a complex of fructooligosaccharides (FOS). This makes yacon a very low calorie fruit/root.

Undigestible sugars always come with a side effect though: they are digested by your gut bacteria, which produce gasses as their major waste product. If you eat too much yacon in one go, you may be in for some discomfort. Most people find it much milder in this regard than the Jerusalem artichoke (or “fartichoke” as it is so aptly called by overindulgers) and the side effects seem to disappear with regular consumption.

Nutritionally, yacon doesn’t offer a lot, although it does have a high level of potassium.

Tuber harvest from a single yacon plant

There are at least nine varieties of yacon in North America, although most suppliers offer one of two very similar unnamed varieties.

Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum)

Remember my rule of thumb above: tastes good/grows poorly vs. grows well/tastes bad? Mashua grows amazingly well in the Pacific Northwest. But it is definitely an acquired taste. Raw, it is kind of radishy and kind of flowery, with some other less describable flavors mixed in. I don’t like it raw, although some people do. Cooked, it is much better, a lot like turnip. It makes a pretty good spicy pickle.

White (Pilifera) Colombian mashua tubers.

You can get 5-10 pounds or more per plant in a mild climate with plenty of fall rain. The form of the plant is very similar to the common garden nasturtium, a close relative. If given something to climb, it will grow up to ten feet tall, but it can also be grown in a pile on the ground, which is the traditional method.

Mashua needs regular watering or good, humus-rich, water-retentive soil. It can die back very quickly if the soil dries out, although it usually recovers in the fall. In fall, it produces a profusion of bright orange, trumpet-shaped flowers that will attract every hummingbird that hasn’t bugged out for the winter (Anna’s Hummingbirds, for one).

Nutritionally, it is similar to potato, but lower in calories and higher in protein. It is very high in vitamin C, anthocyanins, and antioxidants. It seems to depress testosterone levels in rats, although this isn’t well studied. It is possible that it could have a similar effect in humans, although it obviously wouldn’t be here if it kept the farmers who domesticated it from reproducing. Unless you are planning on starting a mashua farm, you probably won’t be growing enough to worry about this.

Orange Ecuadorian mashua tubers

There are at least eight varieties of mashua in North America. Pilifera/White/Blanca is very common and one of the better tasting. The variety Ken Aslet is day neutral and will produce flowers and tubers 4-6 weeks earlier than all of the other varieties, which are short day plants. Other varieties differ primarily in the color of the tubers.

Ulluco (Ullucus tuberosus)

Six varieties of ulluco tubers.

Ulluco takes the opposing position to mashua on the taste vs. productivity spectrum. It tastes great and looks better, but it is not easy to grow in North America. This is the most popular of the Andean tubers other than the potato in South America; you can even find imported canned ulluco in some Hispanic markets in the US.

Ulluco plants grow to be about a foot tall and 18 inches across. They have thick, succulent green leaves, with angular green to red stems and tiny star-like flowers. After the autumn equinox, they produce tubers the size of new potatoes in almost all the colors of the rainbow.

Ulluco tubers are smooth-skinned, with firm flesh that tastes something like a combination of beet and potato. The flesh remains firm even with long cooking times, somewhat like a boiled nut. They work really well in stews or roasted with meat or other vegetables.

Like the rest of the Andean vegetables, ulluco doesn’t like summer heat, but it is even more serious about it. It appears that temperatures above 75 degrees permanently depress yields, even if the plant hasn’t started forming tubers yet. It needs water early and late in the season, but tolerates drought in between. It is very vulnerable to frost and even a light frost may kill all of the foliage.

So, ulluco is a gamble almost everywhere in North America, but what a payoff when you win!

Ulluco plant in flower.

There are at least 19 varieties of ulluco in North America. Beginners should start with the varieties Pica de Pulga or Purple. Other varieties are more challenging.

In Closing…

These four Andean root crops have great potential for cultivation in the Pacific Northwest and other mild climates in North America. Although they are growing in popularity, we still have a lot to learn about growing them.

There has been hardly any effort made to incorporate them into North American cuisine, but these vegetables have many unique attributes that could form the basis of new recipes, rather than mere substitution. If you like to experiment in your garden and in the kitchen, you’ll find many opportunities with Andean vegetables.

Resources

Want to learn more? Here are some options:

The Cultivariable Seeds Blog – My blog, where I go into detail about the growing and breeding of many unusual and forgotten edibles.

Cultivariable Seeds – My seed company, a resource for rare and unusual edibles including Andean root crops.

Radix – Radix has probably done more to popularize oca in recent years than anyone else. The author was one of the first to obtain true oca seed and grow new varieties outside of South America.

Growing Oca – Another fantastic source of information about oca and other Andean crops.

The Radix Root Crops Facebook Group – Join in the discussion or just read along for the most up to date information about these crops.

Thanks again to Bill for putting together this great resource on growing Andean root crops. Do you grow unusable edibles? What has your experience been?

22

Oca leaves look like wood sorrel (in Ontario). Can the leaves be eaten like spinach (or at least like wild greens), or should they be avoided the same way we Do Not Eat Potato Leaves?

Meliad,

Oca and wood sorrel are both members of the genus Oxalis, so you have made the right connection. Oca leaves (and for that matter, all parts of the plant) are edible and taste much like other sorrels – a bit sour. All sorrels get that sour taste from oxalic acid, and the oxalic acid content of oca leaves is much greater than the tubers, so it is best to practice moderation when eating the fresh greens. We add some to salads frequently, using it more as an herb than as a bulk green.

While I’m at it, all parts of mashua and ulluco are edible as well. Mashua leaves are spicy like a radish (or like nasturtium leaves) and we eat a lot of them in salads. Ulluco leaves have slimy sap when raw, which is not very appealing, but they are a lot like spinach when cooked. Yacon is the only plant in the group where you should not eat the foliage. Young stems are sometimes steamed and eaten. The leaves have seen some use as tea, but recent research indicates that prolonged use may cause kidney damage, so I don’t recommend it.

Wow! I have never heard of any of these, but they’re SO intriguing. Love the beautiful colors! I was also going to say that the oca plants look like wood sorrel, if only above ground. We have those growing wild all over our yard, so maybe they’d be a good first choice to try growing.

“There has been hardly any effort made to incorporate them into North American cuisine, but these vegetables have many unique attributes that could form the basis of new recipes, rather than mere substitution. If you like to experiment in your garden and in the kitchen, you’ll find many opportunities with Andean vegetables.”

Sooooo…that means Erica will be growing them?

Sounds like Yacon might the the only one that might work in the midwest. Thanks for the info.

Hadn’t heard of any of these before. Thanks for broadening my knowledge base!

I’m moving to Peru for a year so I was very excited to read this post! Thank you for the information! I wish I had time to grow them in my garden this year, but I’m leaving in mid-summer. I have been wondering about agricultural similarities between the Andes and the Pacific NW. I’m looking forward to tasting all of these root crops and hopefully learning about how to grow them so I an when I get back home! Thanks again!

Hey never heard any of the roots , they look different and colorful are these seriously edible ?

We are a peruvian food growers association and are looking for buyers of our organic grown oca. We are producing our organic oca in the highlands north of peru and have a capacity to grow 5 to 10 tons yearly. We are direct producers and no traders looking to market our product directly to buyers. For more information please contact us. mj16278@live.com